St. Louis Encephalitis

St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) belongs to the virus family Flaviviridae and is related to Japanese encephalitis virus. The virus was first recognized in 1933 when an epidemic in St. Louis, Missouri resulted in over 1,000 cases of encephalitis. Several epidemics have occurred sporadically throughout the U.S. since then, with the majority of cases occurring in eastern and central states.

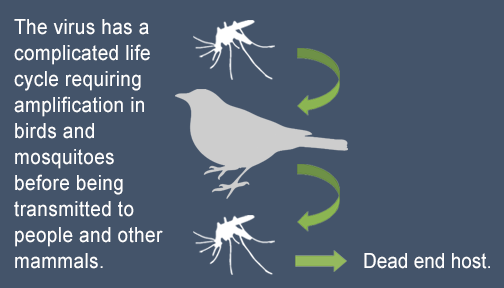

SLEV is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected mosquito. Mosquitoes from the genus Culex contract the virus when feeding on infected birds, and then pass the virus to humans. Wild birds, such as sparrows, pigeons, blue jays, and robins, are the primary hosts of SLEV. Humans are dead-end hosts, meaning that once infected with the virus they cannot transmit it to other humans. Transmission of the virus occurs primarily in late summer and early fall in temperate areas, and occurs year-round in the south.

SLEV is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected mosquito. Mosquitoes from the genus Culex contract the virus when feeding on infected birds, and then pass the virus to humans. Wild birds, such as sparrows, pigeons, blue jays, and robins, are the primary hosts of SLEV. Humans are dead-end hosts, meaning that once infected with the virus they cannot transmit it to other humans. Transmission of the virus occurs primarily in late summer and early fall in temperate areas, and occurs year-round in the south.

Signs and Symptoms of St. Louis Encephalitis

Common Symptoms

- Most people infected with SLEV will show no symptoms, and only a small number of cases result in St. Louis Encephalitis (SLE) disease.

- Those who do become ill may experience fever, headache, nausea, and tiredness.

- Severe infections will result in high fever, neck stiffness, disorientation, and possibly coma, tremors, or even death.

- Mortality ranges from 3% to 30% in those that develop SLE disease and is largely dependent on age.

Treatment of St. Louis Encephalitis

- Care is based on symptoms, as there is no cure or specific treatment for SLE disease.

- For severe cases of illness, supportive treatment includes hospitalization, IV fluids, and respiratory support.

St. Louis Encephalitis Disease and the Elderly

SLE disease is a rare but very serious disease that involves inflammation and swelling of the brain.

The elderly are at a greater risk for both developing the disease as well as experiencing severe complications as a result of the disease. Mortality is estimated between 7% and 24% for those with SLE and over 50, where it is less than 5% for those under 50.

St. Louis Encephalitis Disease and the United States

Prior to the introduction of West Nile virus in 1999, St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) was considered the most significant epidemic mosquito-borne virus in the United States, with cases fluctuating greatly due to periodic outbreaks. Although most infections have historically been reported in central and eastern states, only an average of seven cases per year were documented from 2009 through 2018. The last major epidemic occurred in 1975 along the Ohio–Mississippi River Basin, resulting in nearly 2,000 cases and 142 deaths.

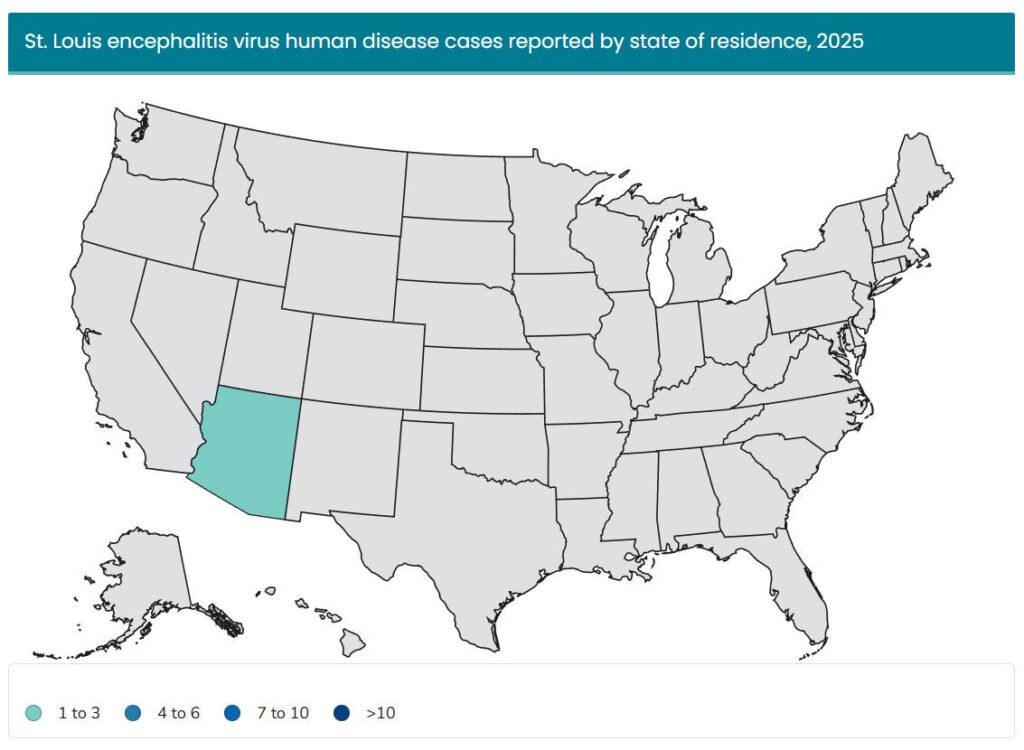

According to the most current CDC data (January 14, 2026), 3 human SLEV disease cases were reported in 2025, including 2 neuroinvasive cases. As with other arboviruses, these data are preliminary and may change as state and local health departments continue surveillance and reporting. Nonetheless, it remains important to monitor SLEV activity, given its potential for sporadic outbreaks in areas where the virus and its mosquito vectors are found.

A Global View of St. Louis Encephalitis

St. Louis Encephalitis virus mainly affects the U.S., though occasional cases have been reported in Mexico and Canada.

Know Your Culex Mosquitoes

Culex species mosquitoes are responsible for the spread of SLEV. Primary vectors in the east include Cx. pipiens and Cx. quinquefasciatus, and in the west include Cx. tarsalis. In Florida, the primary vector species is Cx. nigripalpus.

Culex pipiens, the Northern House Mosquito, is found mainly in the Eastern U.S. It is a medium-sized mosquito with a brownish or grayish body and brown wings, and their larvae thrive in containers of stagnant, polluted water. In addition to SLEV, Culex pipiens is a known carrier of West Nile Virus (WNV), Western Equine encephalitis, and heartworm in dogs.

Culex quinquefasciatus, the Southern House Mosquito, can be found in the southeastern region of the U.S. It is a medium-sized mosquito that is brown in color, and is also a vector of WNV, Western Equine encephalitis, and avian malaria.

Culex tarsalis, the Western Encephalitis Mosquito, is found mainly in the Midwest and West of the U.S. It is a black mosquito distinguished by a white band on its proboscis, as well as white stripes along its middle and hind legs. Culex tarsalis is most active in the few hours after sunset.

Culex nigripalpus are dark, medium-sized mosquitoes and have a subtropical distribution. In the United States, Cx. nigripalpus is found from North Carolina to Texas and are considered the most important disease vectors in Florida. They prefer to lay their eggs in freshly flooded roadside ditches.

Controlling Culex Mosquitoes and St. Louis Encephalitis

An Integrated Mosquito Management (IMM) program is essential to helping prevent mosquito bites and transmission of serious vector diseases in the United States. As part of an effective IMM program, VDCI recommends a 4-pronged approach to target all phases of the mosquito’s life cycle.

1: Public Education

Mosquito control professionals can only do so much, and this is why we rely on a well-educated public in order to have a successful mosquito control program. Educating the public empowers people to take control of the mosquitoes breeding in their back yard and gives them the tools needed to reduce mosquito annoyance.

2: Surveillance

Surveillance allows us to detect mosquito species in a given area as well as any changes in populations. With this valuable data, we are able to more effectively time larvicide applications and more accurately target adulticide activities.

3: Larval Mosquito Control

Our trained field technicians inspect both known sources of standing water and any newly discovered sites for the presence of mosquito larvae. Eliminating mosquitoes prior to their becoming adults is an important element of controlling mosquito-borne diseases because it stops mosquitoes before they acquire the virus and have the opportunity to transmit it to people.

4: Adult Mosquito Control

When necessary, adulticide applications are conducted with EPA-approved pesticides that are used in the safest and most environmentally sound way possible. Additionally, VDCI regularly tests adult mosquitoes and takes all appropriate measures to prevent them from developing resistance; thereby, minimizing the number of applications needed to control the population.