Deep Dive Into the Asian Tiger Mosquito

As if we didn’t have enough mosquitoes in the USA to deal with already, someone had to go and import one from across the ocean. Great – thanks a lot!

Nobody is really sure exactly when the first of these invaders arrived into the USA , but the original recognized North American specimen of the Asian Tiger Mosquito, Aedes albopictus, was collected in June 1983 from a cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee. The species has since become one of the most challenging mosquitoes to control, and brings with it a host of other disease-related challenges.

So what makes this invader such a challenge for mosquito control programs? While most mosquitoes are vampire-like in their avoidance of the sun, waiting until after sunset to seek a blood meal, the Asian Tiger Mosquito can more likely be found actively biting during the daytime in full sunlight. That’s not good. Most modern adult mosquito control occurs after sunset in order to avoid negatively impacting day-flying insects like bees, butterflies, and other popular pollinators. Any pesticides sprayed at night are dissipated by the time the Asian Tiger Mosquitoes take to the wing the next day.

The larvae are equally evasive to typical control programs that are focused on treating larger swamps, ponds, and marshes where most native mosquito larvae thrive. However, the Asian Tiger Mosquito is a “container breeder,” meaning that, like the Northern House Mosquito featured in our December 2015 Mosquito of the Month posting, the larvae thrive in small containers of water. In their native habitats, they lay their eggs in tree holes, rock pools, and even coconut shells, but they’ve adapted to manmade containers as well – any small items that hold water for a long enough time for the larvae to develop.

Imported tires are the likely source of the original invaders into the USA. For example, the first established population was recorded in Texas in 1982, and used tires were identified as their primary larval habitat there. In 2003, the first record of the species in Colorado was from a trap less than 1/10 mile from a tire storage site. Unlike the Texas populations, they didn’t establish in Colorado, probably due to the dry conditions reducing the number of available water-filled containers for egg-laying and larval development. The same is true for the arid regions around Los Angeles, California, where they are believed to have arrived multiple times in oceanic container shipments of cargo such as “lucky bamboo” plants (Dracena spp. – neither lucky nor bamboo), but still have not established large populations. Unfortunately, in more humid environments such as in eastern USA, the Asian Tiger Mosquito has become successfully established, especially in warmer states like Florida. The key to this mosquito’s international spread and successful introduction has been primarily due to the fact that used tires are an ideal place for the larvae to survive, and millions of tires are imported each year into the USA, and travel between states regularly.

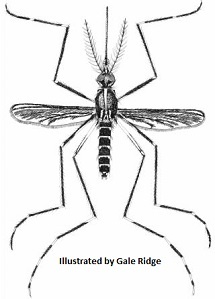

The species was first described in 1894 by F.A. A. Skuse, a young British Entomologist working at the Australian Museum in Sydney, who received specimens from Calcutta where the insect was reported to be “a great nuisance.” Skuse gave his “banded mosquito of Bengal” the Latin species name “albopictus,” meaning “painted white.” As mosquitoes go, the Asian Tiger Mosquito is certainly one of the most gorgeous to look at under a microscope. A velvety jet-black background is marked with contrasting bright, silvery-white patches of scales on the legs, thorax, and abdomen, making this species stand out from the rest when looking at a pile of collected mosquitoes. Especially stunning is the white “racing stripe” that extends from the front of the head, all the way down the back of the thorax to the area between the base of the wings. Wow. She’s a beauty, but she packs a potentially deadly punch.

Beyond being a daytime biting nuisance, the Asian Tiger Mosquito is also capable of transmitting several diseases, including dengue, West Nile virus, chikungunya, and several forms of encephalitis. The presence of this invasive species has become a major public health concern in many locations across the country, especially in the southeastern states.

As humans can now cross the great oceans in hours instead of weeks, the introduction of exotic insects has become a huge concern, and this mosquito is a fine example of why it is important to prevent stowaways from hitching along when we travel around the globe. It is too late to stop this species from invading the USA, and it is likely here to stay, but we can at least keep their numbers in check to reduce their negative impacts. If you live in a part of the country where the Asian Tigers are common, you can do a lot to help reduce their population by inspecting your yard for pools of standing water, no matter how small. Don’t forget to check your rain gutters for clogs that hold water, and even gardening equipment or children’s toys. Eliminating their backyard larval habitats is the key to keeping these invaders under control. Learn more in our source reduction blog.

An important component of any successful Integrated Mosquito Management program is mosquito identification. Should you have any questions regarding mosquito identification, Vector Disease Control International (VDCI) is always available at whatever level of assistance you desire.

Contact Us to Learn More About Effective Mosquito Management Strategies:

Since 1992, Vector Disease Control International (VDCI) has taken pride in providing municipalities, mosquito abatement districts, industrial sites, planned communities, homeowners associations, and golf courses with the tools they need to run effective mosquito control programs. We are determined to protect the public health of the communities in which we operate. Our mosquito control professionals have over 100 years of combined experience in the field of public health, specifically vector disease control. We strive to provide the most effective and scientifically sound mosquito surveillance and control programs possible based on an Integrated Mosquito Management approach recommended by the American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). VDCI is the only company in the country that can manage all aspects of an integrated mosquito management program, from surveillance to disease testing to aerial application in emergency situations.

Since 1992, Vector Disease Control International (VDCI) has taken pride in providing municipalities, mosquito abatement districts, industrial sites, planned communities, homeowners associations, and golf courses with the tools they need to run effective mosquito control programs. We are determined to protect the public health of the communities in which we operate. Our mosquito control professionals have over 100 years of combined experience in the field of public health, specifically vector disease control. We strive to provide the most effective and scientifically sound mosquito surveillance and control programs possible based on an Integrated Mosquito Management approach recommended by the American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). VDCI is the only company in the country that can manage all aspects of an integrated mosquito management program, from surveillance to disease testing to aerial application in emergency situations.